In 2015 eight journalists had been awarded for best reporting on Democracy and Human Rights issues

News Network with the support of the United Nations Democracy Fund (UNDEF) awarded eight journalists for best reporting on Democracy and Human Rights issues. Journalists, based in remote rural districts of Bangladesh who were trained by the News Network, participated in the competition. The award giving ceremony was held on 29 February at News Network Office in Dhaka.

The winners are: First – Maksud Ali, Staff Reporter of The Daily Probaha, Khulna; Second – Mohammad Ali, Correspondent of the Dainik Deshbarta, Dinajpur; Third – Rashidul Islam, Staff Reporter of The Daily Manabzamin, Khulna. Five journalists jointly secured the fourth position. They are Hedait Hossain, Reporter, Jugantor, Khulna; Golam Rabbani Sourov, Correspondent, Bahumatrik.com, Bogra; Amit Roy, Correspondent of Jugantor, Mymensingh; Shihab Uddin Bipu, Correspondent of NTV, Brahmanbaria; Abdur Razzak Rana, Bureau Chief of Dainik Sangram, Khulna office.

Jury members Farid Hossain, Correspondent, Time Magazine and former Bureau Chief of The Associated Press, Dhaka; Shamsuddin Ahmed, Former Joint Editor, The Daily Observer; and Ziaur Rahman, Special Correspondent, The Financial Express; and News Network Editor and CEO Shahiduzzaman, trainers and programme organisers were present at the function.

The Road to Resilience: Press Freedom in South Asia 2015-16 report released

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and the South Asia Media Solidarity Network (SAMSN) marked World Press Freedom Day with the launch of The Road to Resilience: Press Freedom in South Asia 2015-16. The 14th annual report outlines the press freedom in South Asia’s media over the past year.

In the period under review (May, 2015 to April, 2016), 31 journalists, bloggers and media workers were killed. India is emerging as one of the most dangerous countries for journalists as is Bangladesh with an ongoing trend of violent attacks against bloggers.

“Tackling South Asia’s poor record on impunity for crimes against journalists will take more than strong words. For those fighting impunity, the price can be high but there have been positive signs with some arrests and convictions,” the IFJ said.

This year’s report features country reports from the region as will as situation reports on trouble spots and emerging issues, including the current deadly climate facing Bangladeshi bloggers, media freedom struggles in Chhattisgarh state in India as well as Kabul and Kunduz in Afghanistan.

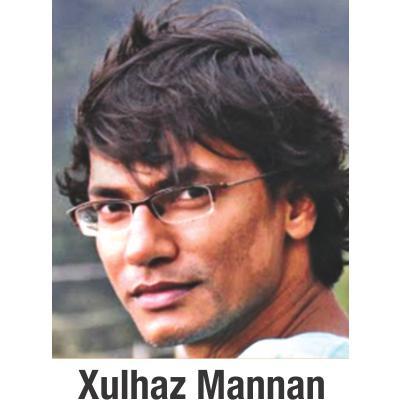

The IFJ said that the resilience of South Asia’s media community is a testament to the state of press freedom across the region. But there are clearly major challenges. In the two weeks leading up to the launch of the report there were two more horrendous murders of individuals working to push the boundaries of freedom of expression in Bangladesh – blogger Nazimuddin Samad and editor Zulhaz Mannan. They are among seven journalists and bloggers killed in the past year under a ruthless killing strategy by fundamentalists and extremists.

Building on the 2015 IFJ gender and media research, this year’s report also documents the growing issues for women in the media in South Asia, with a particular spotlight on online harassment and trolling of women journalists. This focus outlines the experience of independent female media workers, harassed, intimidated, threatened and attacked for simply doing their job.

In the battle against impunity, there were several victories. Pakistan had a win against impunity, convicting the killer of journalist Ayub Khattak, while in Sri Lanka convictions were made and a trial began into the forced disappearance of political cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda.

The report, supported by UNESCO, UNDEF and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, is a key tool for advocacy on issues such as press freedom, impunity and gender equity in the media.

The IFJ added: “Despite the dangers, the journalists in South Asia are not only focussed on presenting the true story to the public, but also are also working equally hard to ensure people’s right to freedom of expression and press freedom. The journalists are taking their battles to the courts, streets and online space for advocacy and building unity and solidarity for campaigning on common causes.”

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

Media Development Programme In Barisal: Fundamental need and rights to be addressed for people in southern Bangladesh

Journalists, media gatekeepers, representatives of Civil Society Organisation(CSOs) and non-government organisations(NGOs) based in Barisal have expressed their opinion to take multiple effective measures to ensure fundamental needs of rural poor. Many of those affected by devastating cyclone Sidar are yet to recover their losses. Besides, continuous river erosion and impact of climate change have compounded the plight of people. The number of displaced people is greater than before. They have also mentioned that most rural people have little access to justice, freedom of expression and information.The ordinary people in the region are trapped in a vicious cycle of corruption. On the other hand, the participation of local people in development activities is not good enough. Even public service deliveries in rural areas have the lack of transparency.

Media people and the CSOs representatives believe that the government alone cannot address all these issues. Integrated efforts are needed to ensure the maximum benefits to local people. So, programmes should be taken on priority basis considering public needs where the participation of targeted people must be granted. They have mentioned it in a News Network media development programme on democracy and human rights issues, supported by the United Nations Democracy Fund (UNDEF).

A ten-day-long programme was organised from 10 to 20 January 2016 at Barisal divisional headquarters to improve the professional capacity to promote and defend democracy and human rights issues. It included five-day training for local journalists; day-long networking meeting with media gatekeepers, including editors, executive editors and news policy planners of local media houses, and four-day media training for CSO and NGO representatives. The initiative was the first of its kind in this region. All the participants found the programme effective and useful. This initiative has given them a better understanding on democracy and human rights issues, and helped increase their capacity to highlight the issues publicly with more confidence.

Additional Deputy Commissioner of Barisal district Md Abul Kalam Azad attended the closing session of journalists training and distributed certificates among the participants. Mr Kalam highly appreciated the initiative and said media is the fourth estate in a democratic society and there was a necessity to further strengthen its role. He urged the journalists to practise fair journalism and report accurately without distorting information.

The gatekeepers of local media houses expressed their dissatisfaction over the distribution of government advertisements. In fact, public advertisements are the main sources of local media’s income but these days most advertisements go to national media houses. They urged the government to revise the distribution policy so local media can play their due role for public welfare. They voiced concern that many of the local media houses may be shut down for lack of advertisement revenue. Editors also proposed raising funds for local and community newspapers to enable them to effectively address social issues.

Speaking on the occasion, the newly-trained journalists and editors raised the issue of their professional safety. They said they often receive threats on their lives. Dozens of journalists fell victims to attacks and torture by miscreants, vested interest groups and law enforcement agencies.The attackers resort to various types of methods to try to silence journalists. For example, a few months ago miscreants tried to kill a journalist by injecting poison into him. He survived as local residents took him to a hospital quickly. Representative of civil society organizations (CSOs) and non-government organisations (NGOs) said local government bodies should not be used to serve political purpose. Instead, these bodies should be motivated to work for society independently, which will provide more benefits to grassroots people.

News Network has trained them to improve their ability to highlight rights-based issues through incident reporting, success stories in relevant fields, conducting case studies and sharing those to mainstream media and in social media for wider coverage, advocacy and campaign. News Network

LGBT magazine editor’s killers left a list of targets

Some important documents left behind by the killers of Xulhaz Mannan and his friend Mahbub Tonoy include a list of targets, police said.

Though the list does not bear any name, the documents say the targets are any individuals or professionals like teachers, students, lawyers and physicians who are giving “false interpretation of Islam, Allah and the prophet”.

Ansar al Islam, which claims to be a local branch of al Qaeda in Indian Subcontinent (AQIS), claimed responsibility for the double murder.

At least seven assailants took part in the operation, and one of them left behind a backpack during a tussle with a police officer who tried to nab him in vain.

The bag contained some documents, a firearm and some bullets, among other things, according to investigators.

Quoting the documents, a top DB official said any individual atheist or LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual transgender) is not their target. Rather those who promote such a cause will be their target.

Xulhaz, a USAID local staff member and also editor of the country’s only known LGBT magazine Roopbaan, and his friend Khandaker Mahbub Rabbi Tonoy were killed by a group of unidentified assailants armed with machetes and firearms inside Xulhaz’s Kalabagan apartment on Monday afternoon.

The Detective Branch of police has been given the charge of probing the killings.

As part of the probe, investigators have started scrutinising the CCTV footage collected from nearby buildings and other evidence found so far.

“We’re giving more focus on ABT [Ansarullah Bangla Team] as the nature of the attack suggests its involvement in the killings,” said the official, asking not to be named, citing ongoing investigation.

Meanwhile, Dhaka Metropolitan Police Commissioner Asaduzzaman Mia yesterday said they would be able to crack this murder case.

He claimed regular crimes like theft, robbery and mugging were under control.

“I don’t want to term it a failure [that police could not catch any of the assailants while fleeing]. But it is pathetic that none of the hundreds of people came forward to stop the killers,” he said while describing how the killers fled after injuring a police sub-inspector.

Some misguided youths are trying to create instability in the country for long through such targeted killings, he said, calling on the city dwellers to provide information about any suspicious tenants.

Parvez Mollah, security guard of the building, said seven youths took part in the mission. They were clean shaven and wore identical clothes.

Four of them entered Xulhaz’s flat on the first floor posing as couriers and directly took part in the killings.

Three others took position at the gate. They took Parvez, another guard and the caretaker of the house hostage inside a ground floor room, Parvez told reporters yesterday.

Four youths then followed Parvez to Xulhaz’s flat, forced into it and hacked Xulhaz and Tonoy to death.

Before that, they stabbed Parvez when he tried to stop them from entering the house.

The Daily Star

Violence against women rises 74%

By Mansura Hossain

Violence against women rose by 74 per cent in 2015 compared to the year before, says a report of BRAC. The report was prepared on the basis of field reports done by BRAC staff working in 55 districts across the country.

The number could be much higher, as 68% of incidents of violence against women go unreported, says the BRAC report.

In 2014, the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) released a national survey of violence against women conducted in 2011.The study found 87 per cent of Bangladeshi married women are abused by their husband.

According to Bangladesh Police website, a total of 17,752 cases were filed in 2010 for violence against women and children. The number of such cases was 21,220 in 2015.

Around100 cases for violence against women were registered in January, 2016.

Representatives of women and children affairs ministry do not disagree with the increase of violence against women while rights activists have expressed their concern over the increase of violence against women.

UN CEDAW committee’s former chairperson Salma Khan told Prothom Alo that Bangladesh men were asked in an ICDDR,B (International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh) whether they feel women to be subservient to them or not.

In reply, both educated and uneducated men, mostly said they think women are in a submissive position to them. This proves men’s attitude towards women, she added.

BRAC’s field report published in June last year shows that the total number of incidents of violence against women in 2014 was 2,873, which has risen to the alarming figure of 5,008 in 2015.

It is 74% higher than the previous year, and this is the highest incidence of violence against women in recent times.

The report also shows poor women are subjected to violence relatively more (54%) because of social discrimination.

Overall, men were responsible for the majority of violence committed against women. It reveals that 88% of perpetrators are men who are family members of the victim women or their neighbours.

According to the BRAC survey, incidents of violence occur more in Comilla, Bogra, Rajshahi, Bagerhat and Satkhira and number of violence increases in May and goes down in January.

The BRAC report was done through its network of ward-level and women-led institutions. The victim or victims’ family, neighbours, and Polli Shomaj members send reports to BRAC head office within 24 hours of identification, and maintain a database.

BRAC’s community empowerment director Anna Minj told Prothom Alo that the family of victim women shows interest to take legal action after the incidents of violence. But, the poor families lose their enthusiasm when influential people force them to withdraw cases.

Eventually, one fourth of the cases reach the final stage. But, victim families withdraw cases negotiating with the accused in exchange of money due to legislative logjam, she added.

Abul Hossain, project director of Multi-Sectoral Programme on Violence against Women under the Ministry of Women and Children Affairs, violence against women is much visible nowadays as people are vocal on the issue.

Bangladesh Mahila Parishad (BMP) prepares report on violence against women based on stories published by national dailies.

According a BMP report, a total of 55,656 women were killed for various reasons in the last 11 years and two months [from January 2005 to February 2016].

Prof Mahfuza Khanam, member of the National Human Rights Commission, told Prothom Alo that state of women and children is also an indicator of development for a country.

Bangladesh is developing day by day but violence against women is also increasing due to the impact of satellite channels, digital culture, and lack of strict laws’ implementation, among others, she added.

Prof Mahfuza Khanam also said an integrated step has to be taken to thwart these incidents of violence against women.

Workplace safety fails to keep pace with industrialisation

By Srinivas Reddy

Every day, 6,300 people die around the world as a result of occupational accidents or work-related diseases — more than 2.3 million deaths per year. The human cost of this daily adversity is vast and the economic burden of poor occupational safety and health practices is estimated at 4 percent of global gross domestic product each year.

While Bangladesh’s industrial base has grown rapidly over the past three decades, workplace safety has failed to keep pace with this development. Though there is no complete data on how many workers suffer occupational accidents in Bangladesh each year, according to the Bangladesh Institute of Labour Studies’ (BILS) newspaper-based survey, a total of 5,909 workers died and 14,413 workers were injured in different occupational accidents over a ten-year period (2002–2012).

For too long, occupational safety and health (OSH) issues have not received necessary and adequate attention, resulting in accidents and loss of life. Things, however, are starting to change and a safety culture is slowly emerging through the efforts of the government, employers and workers organisations with the support of brands, retailers and various development partners.

The government of Bangladesh recently produced the country’s first ever OSH policy and is in the process of finalising a national OSH profile. Work is also starting on a National Plan of Action on OSH. These policy documents provide vital guidance to all national OSH efforts and will help prioritise areas with the biggest potential gains.

At the workplace level we need to ensure that factory managers, supervisors and workers all have basic OSH understanding both in terms of practicalities and rights. The emphasis will always be on prevention, but at the same time all staff members need to know what to do in the face of an accident or emergency. A considerable amount of safety training has been carried out by various stakeholders in recent years. The fall in the numbers of workplace fires and related casualties points to the effectiveness of these actions and the lives and livelihoods which have potentially been saved.

Workers must be helped to better understand their rights relating to workplace safety — the right to use personal protective equipment where necessary, the right to stop hazardous work, the right to ask for help from the labour inspectorate and so on. Employers too have a vital role to play and need to be fully aware of their obligations. Workplace safety should be top priority for them. Money spent on safety is an investment that will not only benefit workers but the business as well. The more effective and efficient labour inspectorate which has emerged since the Rana Plaza tragedy is now better placed to actively enforce regulations relating to safety as well as provide advice and guidance to factory owners on how to meet them.

Another priority is the establishment of safety committees in all factories with more than 50 workers. By bringing worker and employer representatives together, safety committees will play an important function. They will act as a channel for worker participation in improving safety at work and hence the need to provide free and fair opportunities for workers to choose their own safety committee representatives is critical.

In addition, we cannot separate the issue of worker safety from worker rights. Workers who are empowered and aware are fundamental to workplace safety. Trade unions play a vital role in this regard and must be allowed to form and operate freely within all industries. We need to empower workers and their organisations and enable them to become active partners in progress.

On this occasion, I would like to congratulate the labour and employment ministry and especially the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments for organising events in Dhaka and around the country to mark World Day for Safety and Health at Work in Bangladesh for the first time.

I sincerely look forward to this Day becoming the high point of a year-round series of OSH activities. It is the perfect time to reflect on what has been achieved and to energise all our efforts to ensure safe workplaces and decent work for each and every worker in Bangladesh.

The writer is International Labour Organisation’s country director for Bangladesh

The Khapra Ward Day: The Moment and the Movement

No history is mute. No matter how much they own it, break it, and lie about it, human history refuses to shut its mouth. Despite deafness and ignorance, the time that was continues to tick inside the time that is. —Eduardo Galeano

Who are those? If they are communists they should be shot dead. —A police officer, Rajshahi Central Jail, 1950

1

April 24, 1950. It was a sunlit Monday morning. There were 39—according to some, 42—political prisoners in the famous Khapra Ward of Rajshahi Central Jail in the then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Following the jailor’s order, a group of prison-guards opened fire on those unarmed prisoners. They were then in the middle of a hunger strike, protesting inhuman prison practices that ranged from brutal torture to serving sub-standard food—practices enforced by the Muslim League government of Pakistan. Seven communist leaders—Dilwar Hussain and Hanif Sheikh of Kushtia, Anwar Hussain of Khulna, Sudhin Dhar of Rangpur, Bijan Sen of Rajshahi, Sukhen Bhattacharya of Mymensingh, and Kamporam Singh of Dinajpur—were brutally killed in the firing. Other communist prisoners—except a few—were severely injured.

As the Marxist writer-activist Ranesh Dasgupta tells us, among those killed on April 24, 1950, Kamporam Singh was one of the major leaders of the Tebhaga Movement in Dinajpur, while Dilwar Hussain and Hanif Sheikh were the leading organisers of railway and textile mill workers’ unions and movements in Kushtia and Pabna. Bijan Sen and Sudhin Dhar were the fierce revolutionaries of Bengal’s “Agni Joog,” as it used to be called. Both of them had some substantial experience of serving in prison earlier. Following their imprisonment, they exemplarily devoted themselves to building workers’ organisations and movements. Anwar Hossain and Sukhen Bhattacharya were dedicated student activists, while Sudhin Dhar, after 1947, was in charge of an organisation of railway workers in Rangpur. Indeed, as Ranesh Dasgupta further tells us, all of them—while committed to the idea of communism—were variously linked to the communist party itself. I think their togetherness in the Khapra Ward seemed to be representing a kind of communist alliance among peasants, workers, and students, however temporary it might seem.

Thus, among the left in particular, April 24 is known as the Khapra Ward Martyrs’ Day. But that day is more than a fleeting historical or dramatic moment. In other words, that ‘moment,’ I submit, cannot be seen in isolation from the entire history of our national liberation movement itself. In fact, one can trace the history of our liberation movement even earlier than 1952—at least as far back as 1947-1950. For, to be historically faithful, it was precisely at that post-‘independence’ conjuncture in Pakistan that the initial waves of resistance to its ruling classes came from peasants, from workers, and—however outrageous it may sound to some mainstream partisan historians today—from communists themselves, their internal differences and tactical pitfalls notwithstanding.

Indeed, our standard or official or middle-class historical narratives of the Liberation Movement of Bangladesh—which was by no means a one-off event—both reveal and conceal. Surely they keep revealing the roles of certain leaders and individuals again and again, important and even heroic as they are. But those historical accounts in many instances also remain suggestively silent about the roles of the genuinely oppressed—women, peasants, and workers, among others, for instance. Indeed, without their protracted struggles, their insurrections, their uprisings, and their sacrifices at various levels and various times, Bangladesh would not have come into being as a distinct nation-state in 1971. Indeed, the true protagonists of our Liberation Movement of 1971 were common, ‘ordinary’ people themselves, the majority of whom were peasants and workers.

But, then, there are even other years and other names that also remain virtually or relatively absent in our standard historical narratives. In fact, history-writing itself continues to remain a battlefield of conflicting and competing interests—even a site of the class struggle—while absences, silences, and gaps in the writing of our history are by no means politically and ideologically neutral or innocent.

2

So, then, do we know who Lutfar Rahman was? Or Mozam Mollah and Fani Guha, for that matter? These names, among many others, take us back to a particularly turbulent period in the history of people’s resistance in the then East Pakistan, a period not often heeded, let alone scrutinised. Lutfar Rahman was a communist activist from Jessore. He was arrested in 1939. He was accused of the ‘crime’ that he used to read and disseminate communist literature. After the creation of Pakistan as a nation-state, Lutfar was arrested again, in 1949. He actively participated in hunger-strikes—then almost generally reckoned an ‘effective’ tactic of resistance by communists—against the oppressive prison-system of Pakistan and by extension, against the Pakistani ruling class. While in prison in 1950, Lutfar Rahman was infected with tuberculosis. Witnessing—and being subject to—the kind of brutal persecution that went on inside prison without any signs of abatement and was particularly perpetrated on his fellow communists, Lutfar went literally insane at one point. Although he was released on July 13, 1950, physically and mentally tortured and devastated as he was, he died at the prison gate itself. Obviously, it was not a natural death but a murder.

And then there was Fani Guha. He was Secretary of the Dhaka District Communist Party. He was arrested in 1949. Because of his persistent participation in hunger-strikes inside jail—there were as many as four hunger-strikes, spanning a total of 181 days during the period between 1949 and 1950, in which communists and left activists participated to varying degrees—his arteries got brutally pierced and thus he died soon after he had been transferred to the Mymensingh jail. Mozam Mollah—who was a fierce militant of the Tebhaga movement in the Narail area of Bangladesh—also died in prison in 1949 because of inhuman police brutality perpetrated on him, while Bishnu Bairagi was beaten to death in the Khulna jail in 1950. Also, women prisoners—communist as they were—were variously tortured. My own former teacher Nadera Begum, who herself was a communist prisoner in the Dhaka Central jail, and who was tortured by the police there (she was released in 1950 and later became a professor in the Dhaka University English department), told us quite a few of those horror stories of torture in prison.

One can surely cite many other examples, while I cannot traverse the entire range of even relevant events here owing to space constraints. But I think the main point comes out clearly: the entire prison system of the then East Pakistan, the coercive apparatus of the post-independence Pakistani ruling class, decisively targeted Bengali communists, left activists, and peasant leaders, who were then perceived to be the most dangerous enemies of Pakistan. Many of them were even called or considered “deshodrohee” (treacherous to the country), for instance. Motiur Rahman’s 2015 book called Khapra Ward Hottakando 1950 [Khapra Ward Killings 1950]—well-researched as it is—calls attention to an official press note that explicitly described or declared the communist revolutionaries in 1950 as “deshodrohee,” or as anti-Pakistan elements to be eliminated.

3

Indeed, what the communist prisoners did in 1949-1950 cannot be simply reduced to a case of adventurism and thus glibly or quickly dismissed as a total failure, although there were certain elements of adventurism of which one might be critical. As Salud Algabre, the feminist leader of the Sakdal rebellion in the Philippines, once memorably put it, “No uprising fails [in the final instance]. Each one is a step forward.” And what the communist inmates did inside various prisons in the then East Pakistan—particularly in Rajshahi Central Jail, where police brutalities and physical torture assumed unparalleled proportions—can be seen as an organised movement in its own right. Owing to space constraints again, I intend to make only a few general points about this movement here.

In the first place, the movement of the communist prisoners—by organising hunger strikes in almost headlong succession—repeatedly resisted inhuman prison conditions, which themselves were seen as examples of organised state violence. For the communists, prison itself turned out to be an explosive site of class struggle. Some works—particularly Badruddin Umar’s Purbo Banglar Bhasha Andolon o Totkalin Rajneeti [The Language Movement of East Bengal and Politics at the Time] and Abdus Shaheed’s Kara Smriti [Prison Memoirs]—memorably depict the notorious prison conditions prevailing at the time in the country. In this instance, the organised communist resistance—the first one of its kind—to the coercive apparatus of Pakistan amounted to resisting the very state of Pakistan which was found to be oppressive by and large.

But the larger significance of the Khapra Ward movement, I think, resides in the fact that the communist prisoners derived their energy and inspiration from at least 4 remarkable peasant movements—the Tebhaga Movement (1946-47), the Tonko Abolition Movement (1946-50), the Nanakar Abolition Movement (1920-50), and the Nachol Movement (1949-1950)—movements that of course decisively and exemplarily underlined the land as the site of the class struggle for the toiling masses. But some of the demands advanced by those peasant movements remained variously unmet even after the independence of Pakistan in 1947.

Thus it was strategically clear to the communists at the time—and they were among the first ones to have immediately realised—that the independence of Pakistan was a fake one, and that the state of Pakistan was an undemocratic, feudal, militaristic, colonialist, and pro-imperialist at the same time. And they wanted to dismantle this state in favour of the emancipation of peasants and workers. It is true that the organisations of the communist party were getting increasingly strong and gathering remarkable momentum in East Bengal between, say, 1937 and 1947. But later on, many, if not all, communists in East Bengal turned to the path of the armed struggle—inspired particularly by B.T. Ranadeev of the Communist Party of India, for instance—without, however, adequately considering their mass-bases and the strengths of their opponents, among other issues. The prices the communist movement had to pay subsequently were enormous, to say the least.

The above topic itself calls for an extended engagement into which I cannot go now. But—regardless of their tactical pitfalls and the degree of their detachment from the people themselves—the Khapra Ward communist prisoners, among other prisoners of course, at least clearly provided the message that the Pakistani ruling class would not go unchallenged by any means. It was a beginning of sorts. It marked the beginning of anti-Pakistan resistance. It’s not for nothing that the Khapra Ward prisoners subsequently served as an inspiration to the left, and that they were remembered fondly and respectfully by a lot of freedom-fighters during the Liberation War of Bangladesh, people’s war as it was.

The Khapra Ward communist prisoners—in their own ways—also fought in advance, so to speak, for the three announced principles—I call them “revolutionary” principles—that later guided our national liberation movement in 1971, for instance: equality, justice, and dignity. As long as these three fundamental principles remain relevant—and indeed they remain relevant, given that the majority of the people in our country, including women, peasants, workers, and minorities, have not yet achieved their economic, political, and cultural freedom in our country—the Khapra Ward communist prisoners remain with us in the history of our struggles against all forms and forces of oppression and exploitation.

The writer is Vice-President of US-based Global Center for Advanced Studies and Associate Professor of Liberal Studies/Interdisciplinary Studies at Grand Valley State University in Michigan, while he is currently Scholar-in-Residence at the University of Liberal Arts-Bangladesh (ULAB).He writes in both Bangla and English.

Source: The Daily Star